Back to Spheres of Influence? Great-power ambitions and the politics of permanent emergency

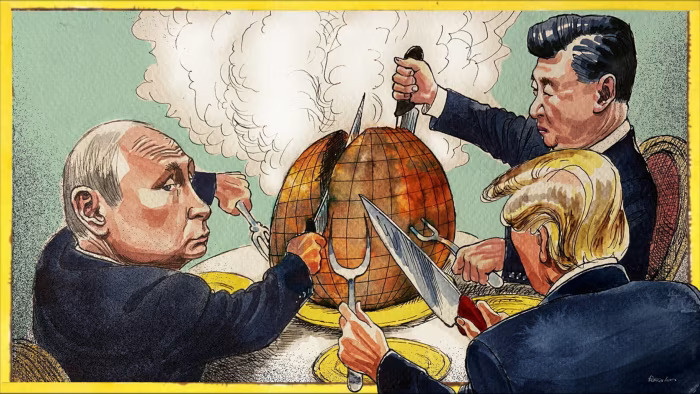

The question is no longer whether great-power rivalry is intensifying. It is whether the world is reorganizing around a Cold-War style logic—regional hegemons policing their neighborhoods, weaponized interdependence fragmenting the global economy, and “states of exception” normalizing rights restrictions at home—with inequality and polarization accelerating as a result. This is not necessarily what the potential eastern hegemons were looking for, but will they miss the chance to pick it up if the chance is solidified?

Andrianos Charalambous

1/18/202610 min read

Back to Spheres of Influence? Great-power ambitions and the politics of permanent emergency

by Andrianos Charalambous

The White House has put an old idea back at the center of American strategy: spheres of influence. In its December 2025 National Security Strategy, the Trump administration explicitely declares that: "We (the Trump administration) want to ensure that the Western Hemisphere remains reasonably stable and well-governed enough to prevent and discourage mass migration to the United States; we want a Hemisphere whose governments cooperate with us against narco-terrorists, cartels, and other transnational criminal organizations; we want a Hemisphere that remains free of hostile foreign incursion or ownership of key assets, and that supports critical supply chains; and we want to ensure our continued access to key strategic locations. In other words, we will assert and enforce a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine".

In recent weeks, that doctrine has collided with an already combustible international environment: U.S. military intervention in Venezuela and legal fallout at the United Nations, furhter tariff coercion against European allies tied to a Greenland dispute, Russia’s continued war pressure in Europe, and China’s expanding gray-zone coercion against Taiwan—including a first-time drone incursion into Taiwanese airspace over the Pratas/Dongsha islands.

At the same time, Washington has announced a mass pullout from international organizations, and—most consequentially for long-term collective security—withdrawal from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and participation in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), moves criticized by the UN climate chief and noted formally by the IPCC. But most of all, political analysts and affected governments seem to be alarmed by one thing - the emergent possibility of the clash between two NATO allies (if not more), thus the degradation of what has been keeping the alliance together. After all, is NATO a tool worth preserving for the US, or is it becoming a liability in the Trump administration's conquest towards "Western hemisphere hegemony"?

The question is no longer whether great-power rivalry is intensifying. It is whether the world is reorganizing around a Cold-War style logic—regional hegemons policing their neighborhoods, weaponized interdependence fragmenting the global economy, and “states of exception” normalizing rights restrictions at home—with inequality and polarization accelerating as a result. This is not necessarily what the potential eastern hegemons were looking for, but will they miss the chance to pick it up if the chance is solidified?

The key concepts: what “Cold War” and “hegemony” actually mean here

Cold War, then “cold-war politics”

The Cold War was a historical period; today’s “cold-war politics” is a method: sustained rivalry managed below the threshold of direct great-power war, using coercion, crisis signaling, and competition through peripheries.

Two landmark historians show why the analogy is sticky:

John Lewis Gaddis in his book "The Cold War: A New History" emphasizes how nuclear risk made the Cold War a problem of crisis management and indirect competition rather than direct superpower war, while awakening fresh nightmares of terror and creating frames for technologically advanced aggression.

Odd Arne Westad in his book "The Global Cold War" argues that the Cold War’s deepest consequences played out in the peripheries—Asia, Africa, the Middle East—where great-power rivalry fused with local conflict, proxy wars, and state formation, in a conquest of influence and resource security.

That pairing describes much of the current atmosphere: strong incentives to avoid U.S.–China or NATO–Russia direct war, paired with expanding coercion and “gray-zone” pressure in contested regions.

Hegemony: power plus legitimacy, not power alone

“Hegemony” isn’t just dominance. It’s dominance that is stabilized by rules, institutions, and ideas that make hierarchy feel normal and/or inevitable.

Two theoretical traditions are especially useful here:

Gramsci’s hegemony is built through consent as well as coercion, with civil society shaping “common sense” so that domination appears legitimate.

Keohane’s argument in After Hegemony is institutional: even as hegemonic power wanes, international regimes can preserve cooperation by lowering transaction costs and uncertainty. Weakening institutions raises the price of cooperation and accelerates fragmentation.

Read together, “America First” and the consequent tariff war as a tool in an extensive toolbox of coercion tools, is not just a change in priorities—it is an attempt to reset what counts as legitimate power (Gramsci) and to renegotiate the institutional constraints through which power is exercised (Keohane).

The Monroe Doctrine returns—this time as explicit strategy

The U.S. government’s official historical framing of the Monroe Doctrine (1823) emphasizes European non-colonization and non-intervention in the Americas—a “separate spheres” warning. It is particularly important here to take into consideration the vast difference in the context of this reform with its alleged reintroduction - a newly established independent federal state through a severe decolonial struggle and the global leader the USA is today.

The December 2025 NSS goes further than history: it operationalizes a hemispheric sphere in contemporary terms. It says the U.S. wants a hemisphere free of “hostile foreign incursion or ownership of key assets,” and spells out the policy toolkit—military “readjustment,” border deployments, and even tariffs as “powerful tools” of commercial diplomacy.

That is spheres-of-influence language in near-plain English.

When doctrine becomes action: Venezuela, Greenland, Panama

In early January, U.S. forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and brought him to the United States to face criminal charges. Legal experts immediately disputed the legality under international law and the issue naturally became a focal point at the United Nations.

This matters beyond Venezuela: it normalizes the idea that hemispheric enforcement can override core post-1945 constraints on the use of force—especially when the enforcing state faces few practical consequences. This is of course not the first time the US proceeds with such actions (some scholars put the number between 50-80 times in the past century), but it can be said that this is certainly one of the most blatant examples. Reuters reported UN human rights officials warning the intervention makes the world less safe, precisely because it weakens the taboo against unlawful force.

In Europe, Reuters and AP report the Trump administration threatened—and in some coverage imposed—tariffs on European allies linked to a Greenland dispute, prompting EU leaders to warn of a “dangerous downward spiral” in transatlantic relations.

The economic logic is immediate: markets face volatility when tariffs become a geopolitical lever. The political logic is deeper: alliance relationships start to resemble transactional bargaining—exactly the kind of institutional erosion Keohane warns can raise cooperation costs and accelerate fragmentation.

To further the theme, Trump has repeatedly threatened Panama with military action "if needed" to seize control of the Panama Canal, which he claims was built by Americans - a claim that is actively contested both about its factuality and its legitimacy as an argument.

Russia and China: regional hegemony, global disruption, or global ambition?

A useful baseline comes from John Mearsheimer’s “offensive realism”: great powers strive for regional hegemony and work to prevent peer hegemons elsewhere; oceans and distance make true global hegemony exceptionally difficult.

That framework helps clarify Russia and China—while also showing where each exceeds a purely regional play.

Russia’s war posture points strongly to regional hegemony: a bid for veto power over neighbors’ alignment choices and the security architecture of Eastern Europe. But Russia also projects global influence through energy leverage, sanctions adaptation, and diplomatic disruption rather than by building a full alternative world order.

But to claim that Russia, even in its contemporary state of affairs, strives to become the hegemon of the Eastern Hemisphere, would be a wild misconception. Even if in sporadic instances in rhetoric and in action, Russia imposes its agenda through coercion in the surrounding region, even vocally reminding the people of the Soviet era, it has never acted towards the reistablisment of such a block of nations, or for regional domination. This, of course, comes in contrast to what most of the Western (European and US) media and institutions want us to believe, but it is never the less factual.

China’s military pressure on Taiwan illustrates regional dominance logic. Reuters (17/01/2026) reported a Chinese reconnaissance drone entered Taiwanese airspace over Pratas/Dongsha for several minutes at an altitude beyond Taiwan’s air defense reach; the Financial Times characterized it as a first-time threshold crossing designed to test defenses and normalize intrusion.

But China’s ambitions may not stop at the region. Rush Doshi’s "The Long Game" argues China has pursued a sequential strategy: first blunting U.S. power, then building alternatives, and increasingly expanding influence to reshape order beyond Asia.

So, if Mearsheimer gives a strong “regional hegemony is the ceiling” hypothesis, Doshi offers a competing interpretation: China as a rising power seeking regional primacy plus systemic redesign. Those two lenses capture today’s central strategic disagreement.

This comes today with the normalisation of China as a global financial giant - one that managed to stress the taken-for-granted US global dominance, through a meteoric rise in its production capacity as well as in its capacity to seamlessly export what it produces to every corner of the globe. Nevertheless, it also comes with a vocal and categoric refusal by Chinese spokespersons that China is trying in any way to compete explicitly with the US or become a neo-colonial power in any way.

However we may see it, Russia invading Ukraine for the reasons the Putin regime has claimed and China trying to impose its control over Hong Kong and Taiwan, is a far cry from attempting to secure the hemisphere for themselves.

Middle powers in the new atmosphere: India, BRICS, and multi-alignment

This is not a world of automatic binary alignment. Many states are practicing multi-alignment—maximizing flexibility across blocs.

Indian foreign policy is widely described as “strategic autonomy,” and Jaishankar’s The India Way has become a reference point for the idea that India should build multiple partnerships rather than rely on any single patron. Carnegie’s analysis treats this approach as a coherent grand strategy for a multipolar environment.

BRICS expansion continues to shift the diplomatic map. AP reported Indonesia’s admission as a BRICS member, and Reuters reported Indonesia joining the New Development Bank (NDB)—part of the broader effort to widen development finance options and reduce choke-point dependence.

The NDB itself emphasizes financing in both local and hard currencies, and its investor materials highlight its development of financial markets in member states—an architecture that fits a fragmentation era where currency risk and sanctions risk are central.

In hegemony terms: BRICS is less a unified “new hegemon” and more a bargaining arena within what Acharya calls a multiplex world, where multiple orders and institutions overlap rather than converge under one rule-set.

The world economy: fragmentation, coercion, and a higher-cost future

Fragmentation is no longer speculative; it is being measured and modeled.

The World Economic Forum’s report on global financial system fragmentation maps how geopolitics and regulatory divergence can fracture payments, compliance systems, and capital flows—and warns of significant costs if fragmentation accelerates.

The CEPR Geneva Report on international financial fragmentation argues geopolitical tension is eroding the cooperative order that underpinned decades of integration, reshaping payment systems and reserve currency patterns and weakening coordinated crisis response.

The IMF has warned repeatedly that geoeconomic fragmentation carries meaningful output costs and threatens the benefits of integration.

The mechanism linking rivalry to economics is best captured by Farrell and Newman’s “weaponized interdependence”: states that sit at network hubs (finance, data, supply chains) can convert global connectivity into coercive chokepoints. If you were looking for a word about Iran, you will find it here. I choose not to go further into this discussion, because it breaks the context of the "Hemisphere Hegemony", but having made this realisation, it is important to note that Trump also seems to be avoidant of this issue, despite his vocal declarations. He seems to be "constraining himself" from a (new) military intervention and prefers to infuse an already turbulent situation on the ground for the Iranian autocratic regime.

That is “cold-war politics” with modern infrastructure: not just missiles, but payment rails, export controls, shipping insurance, cloud systems, and standards-setting.

Inequality: why fragmentation tends to make the rich richer and the poor poorer

The distributional effects of this world are not neutral.

The World Inequality Report 2026 documents extreme wealth concentration: the top 0.001% (about 56,000 adults) hold three times more wealth than the bottom half of the world’s adult population combined. Another key fact, is that the income of the middle-class is by far at the bottom of the growth scale, increasingly pushing it closer to the bottom 50%, thus essentially eradicating it.

In a fragmented world:

trade shocks and tariff cycles raise prices and volatility,

sanctions and “de-risking” redirect investment to politically safe jurisdictions,

capital mobility and asset diversification shield top wealth holders,

while poorer households absorb inflation, weakened labor protections, and austerity pressures.

This is consistent with the broader “winners and losers of globalization” debate, often associated with Milanović’s work and the “elephant curve” narrative: integration and disruption produce uneven gains that can become politically explosive.

The “state of exception”: how permanent emergency suppresses rights

A world of constant threat also changes domestic governance.

Carl Schmitt’s classic definition—quoted in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy—holds that “sovereign is he who decides on the exceptions,” emphasizing that emergency can place executive decision above normal law.

Giorgio Agamben’s "State of Exception" extends this into a warning about modern democracies: emergency measures designed as temporary become a normal paradigm of government, thinning rights protections and expanding coercive capacity. A major review essay in the European Journal of International Law situates Agamben’s argument precisely in that shift: legalized suspension of legal limits in the name of necessity.

In a rivalry era, “exception” politics spreads easily: migration, protest, surveillance, and “national security” become umbrella justifications—particularly when external threats are salient and economic anxiety is high.

Polarization and the far right: why this atmosphere is fertile ground

The bridge from inequality and emergency politics to far-right growth is well developed in the literature:

Seymour Martin Lipset in his seminal 1959 article, "Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy," argues that democracy is stronger, more stable, and more likely to be sustained in developed (and fair) economies

Norris & Inglehart argue authoritarian-populist support can grow through cultural backlash as societies liberalize and some groups feel status threat.

Eatwell & Goodwin explain national-populist success through the “four Ds”: distrust, destruction, deprivation, de-alignment—long-run conditions amplified by crisis.

Put these together with the “state of exception” dynamic and you get a powerful feedback loop: fear and insecurity justify tougher governance; tougher governance narrows rights; narrowed rights deepen grievance and distrust; grievance fuels polarization and radical-right normalization.

A system-level reading: from global order to competitive regional hegemonies

The Trump administration is unusually candid about prioritization: it explicitly argues that sustained attention to the “periphery” can be a mistake and that U.S. focus should be on core national interests—starting with the hemisphere.

This fits a broader diagnosis in international-order scholarship: the American-led order is not only a distribution of power but globalisation seems to have moved from a triumph for Western liberal democracies to a crisis of authority and legitimacy, as Ikenberry has argued.

Meanwhile, regional logics are becoming more decisive, consistent with Buzan and Wæver’s regional security complex theory: security interdependence clusters geographically, and global powers are often “drawn in” by regional dynamics rather than wholly controlling them.

In practice, this looks like an emerging model of competitive regional hegemonies:

U.S. hemispheric enforcement,

Russia’s coercive neighborhood strategy,

China’s expanding near-seas pressure with potential systemic ambition,

and middle-power multi-alignment through platforms like BRICS and diversified partnerships.

That structure is colder, costlier, and more unequal—and it creates precisely the political conditions under which rights shrink and radicalization grows.

Finalising this long association, the question that emerges is: where does the European Union stand in all of those developments? This shound now be increasingly concerning Cyprus as the new president of the European Council, but of course the Union itself. This now makes it the most pressuring question for my next article...