The curious case of considering the US military intervention to Venezuela as a curious case

The wobble matters because it quietly normalizes a dangerous idea: that the law becomes optional when the target is unpopular and the perpetrator "larger than International Law"(?)—and that “we’re still thinking about it” is a (im)morally neutral position rather than a political choice. If the rules are treated as optional the moment a powerful state decides they are inconvenient, then the world is not debating legality; it is rehearsing permission.

Andrianos Charalambous

1/8/202614 min read

The curious case of considering the U.S. military intervention in Venezuela as a curious case

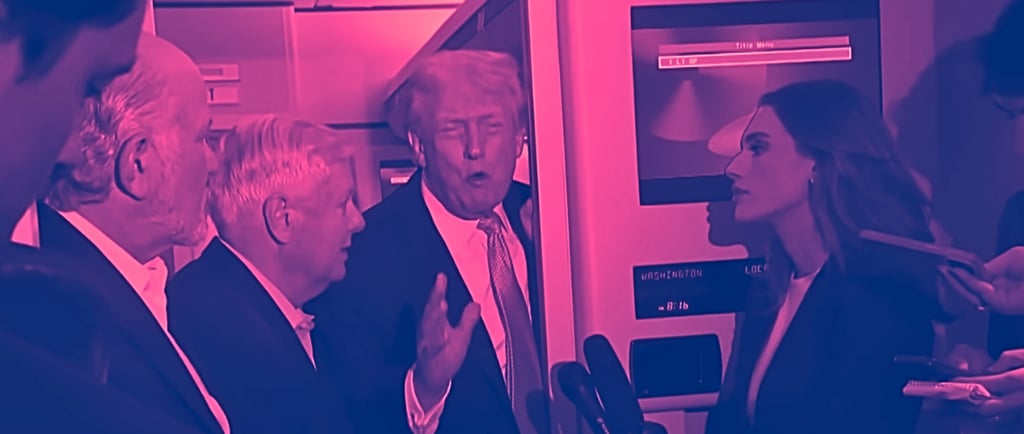

I keep coming back to how strange the global conversation has been in the past few days. Not because the event is hard to describe—by most public accounts, U.S. forces carried out a strike-and-capture operation in Caracas that ended with Nicolás Maduro transferred to U.S. custody—but because so many officials and headlines treated the core question as if it were a philosophical puzzle rather than a rules-based one. [1][2]

In the transcripts I worked through, the tension is blunt. One line of argument says the intervention is about oil, said out loud and repeated without embarrassment. Another line of argument says the issue is not Maduro’s character, but whether any state has the right—by force, coercion, or economic strangulation—to decide another country’s political future. I don’t think those views are mutually exclusive. I think they describe two pillars of power that have repeatedly overlapped for more than a century: regime change and energy interests.

And Venezuela, in 2026, is where the overlap becomes impossible to ignore.

What happened (and why it instantly became a legitimacy fight)

Here’s the core sequence as it has been publicly reported:

The U.S. military targeted and detroyed multiple vessels in international waters, in the span of late 2025, claiming that they were navigated by "Venezuelan narcoterrorists".

A U.S. operation in Venezuela resulted in Maduro’s removal from the country and transfer to the United States, followed by an initial U.S. court appearance and a not guilty plea. [1][2]

Almost immediately, the public messaging pivoted toward Venezuelan oil—down to specific barrel figures, claims of indefinite control of sales, and plans to park proceeds in U.S.-controlled accounts while U.S. companies are invited in. [3][4][5]

I don’t need to romanticize Maduro or demonize Trump to recognize the pattern: when a major power uses force and then talks about controlling a country’s main revenue stream, the world will (should) interpret it as something bigger than “law enforcement.”

A critical note on the world’s “confusion” about legitimacy

What’s been most revealing isn’t only the operation itself, but the global performance of uncertainty that followed: diplomats and headlines twisting themselves into knots to decide whether this was “legitimate,” as if legitimacy were a vibes-based referendum rather than a rules-based question. What has stood out isn’t only what happened—it’s the way parts of the international community and major news ecosystems have treated the aftermath like a philosophical puzzle.

Even leaders who despise Maduro’s rule leaned on hedged language—“complex,” “unclear,” “hard to judge”—that protects alliances more than it protects rules. And a lot of mainstream coverage treated legality like a coin toss, despite the fact that the baseline rule is not obscure: force is prohibited except under narrow exceptions. [6]

Some outlets frame it as a debate between legality and legitimacy, as though legitimacy can be separately laundered after the fact. But under the UN Charter framework, legality isn’t a vibe; it’s a structure: no Security Council authorization, no self-defense triggered by an armed attack, no recognized pathway for forcibly removing a head of state from his territory and “relocating” him for prosecution. And yet, many governments have responded with careful fog—statements of “concern,” requests for “more information,” EU calls for “de-escalation,” and a studied reluctance to name the action plainly. This is not uncertainty about facts; it is strategic hesitation in public.

That wobble matters because it quietly normalizes a dangerous idea: that the law becomes optional when the target is unpopular and the perpetrator "larger than International Law"(?)—and that “we’re still thinking about it” is a (im)morally neutral position rather than a political choice. If the rules are treated as optional the moment a powerful state decides they are inconvenient, then the world is not debating legality; it is rehearsing permission.

The legal frame I refuse to pretend is optional

I’m going to say this directly: the baseline rule is not ambiguous.

Article 2(4) of the UN Charter prohibits the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.

The Definition of Aggression (UNGA Res. 3314) reinforces that aggression includes armed force used against another state’s sovereignty or political independence.

In the Americas specifically, the OAS Charter commits states to non-intervention and renounces force except in self-defense consistent with existing treaties.

And historically, when the U.S. tried to justify interventions through creative categories, the ICJ’s Nicaragua judgment (1986) remains the landmark reminder that “helping” an opposition does not convert coercion into legality—and that the principle of non-intervention collapses if outsiders can intervene whenever they prefer a different faction.

If someone wants to pivot to humanitarian logic, they run into another wall: R2P (Responsibility to Protect) is not a unilateral permission slip. It is anchored in collective action through the Security Council, on a case-by-case basis, and limited to atrocity crimes. But even under legitimate applications, this is a heavily disputed approach that is often manipulated by powerful international actors to disguise military intervention as a "humanitarian mission".

So when I watch public discussion drift into “maybe it was legitimate”, I hear something else: the slow normalization of “might makes right,” dressed up as analysis.

Venezuela isn’t a crisis state—it’s an energy state

Venezuela keeps reappearing in the strategic imagination for a structural reason: it is widely assessed as holding the world’s largest proven crude oil reserves, around 303 billion barrels, even if much of that crude is extra-heavy and technically difficult to produce. [7]

In an oil state, controlling the oil sector isn’t just “getting barrels.” It means controlling the main channel through which the state funds itself, buys loyalty, and survives pressure.

And that brings us to the two pillars.

1. Regime change and 2. Oil interests

I don’t think every U.S. intervention can be reduced to one motive. But I do think U.S. policy has repeatedly moved along two tracks that often merge: (1) changing regimes and (2) securing energy leverage. Sometimes one dominates. Sometimes they interlock so tightly that separating them becomes an academic exercise.

When I say “regime change,” I’m not only talking about invasion. I mean the broader menu: covert action, proxy warfare, political engineering, sanctions designed to destabilize elites, recognition strategies that shift the meaning of sovereignty, and—when leaders decide the moment has come—direct force.

Iran, Vietnam, Nicaragua: the long shadow of “indirect” overthrow

Iran (1953) is the foundational reference point because it captures the core logic: a government challenges external interests and the structure of resource control; covert action helps remove it; a long tail of instability and mistrust follows. It’s a regime-change story that later generations read as a warning about blowback—and it sits right at the intersection of governance and oil. [8]

Vietnam demonstrates how regime change can be dressed up as “containment” or “credibility.” Once war becomes about the political character of a state—who governs and which ideology wins—intervention becomes regime engineering whether or not anyone uses the phrase. The lesson I take from Vietnam isn’t simply “war is costly”; it’s that when political outcomes become military objectives, legal and moral constraints tend to bend—slowly at first, then all at once. This was also the war that shaped the anti-war movement in the U.S. and one of the most brutally characteristic instances of institutional anti-communism paranoia.

Nicaragua (1980s) shows another recurring design: sustain pressure through proxies and deniability, then fight over legality and oversight after the fact. It’s the classic example of how a regime-change mindset can keep running even when constraints exist on paper—because the real contest shifts to informal channels, third parties, and bureaucratic workarounds. [9]

Iraq (2003) and Afghanistan: when regime change is only the opening move

Iraq (2003) and Afghanistan (2001) are the modern reminder that toppling a government can be the easiest part. The long tail—occupation politics, legitimacy crises, insurgency dynamics, institutional collapse—has a habit of outliving the original justification. These cases are where “regime change” stopped sounding like a discrete event and started looking like a governance project with no clean exit. (And that matters for Venezuela because “running” a country is never just a slogan; it’s an administrative reality with consequences.)

Venezuela before 2026: pressure politics and the slow build to escalation

In Venezuela, that pattern already had a long runway: U.S. involvement around the 2002 coup attempt, long-running funding and political engagement, the escalation of sanctions, and the 2019 recognition of Juan Guaidó as interim president—an act that had material consequences for overseas assets and control claims.

One marker that matters is the U.S. decision in 2015 to declare a national emergency with respect to Venezuela using “unusual and extraordinary threat” language, creating a durable legal framework for sanctions escalation. [10]

From there, the arc is familiar: broader financial isolation, strategic licensing, recognition battles, and persistent efforts to shape who governs. Then came 2026—when coercion stopped being mainly economic and political, and became explicitly military.

Oil interests as strategic leverage (not always the cause, often the accelerant)

I’m cautious with the sentence “it’s all about oil.” It can become lazy. But I’m equally cautious about pretending oil is irrelevant when leaders speak about it obsessively and when post-intervention policy immediately targets oil revenue channels.

Oil matters in three ways:

It shapes who can finance power (rents fund stability or coercion).

It shapes global leverage (buyers, refiners, shipping, sanctions).

It shapes postwar rewards (contracts, access, influence).

The missing piece people tend to forget: the U.S. already cut Venezuela off—then returned to “we want the oil”

For decades, Venezuela was a major supplier into U.S. refining—especially heavy-crude processing along the Gulf Coast. Then, after January 2019 sanctions on Venezuela’s state oil company, U.S. imports from Venezuela stopped shortly afterward. [14][15]

That’s why the January 2026 pivot is so revealing. After using state power to choke off trade, the same political world reappears with a new message: we’re taking control of Venezuelan oil again—including public talk of tens of millions of barrels, “indefinite” control over sales, and proceeds held in U.S.-controlled accounts. [3][4][5]

If I’m trying to understand motive, this sequence matters more than any slogan: first, squeeze the oil state’s lifeline; then, when force is used, treat oil as the centerpiece of the post-operation plan.

Venezuela didn't "fail" - it was "failed" - Sanctions as economic warfare

I’m not going to pretend the Venezuela crisis was “caused by sanctions.” That would be historically unserious. Venezuela’s internal governance failures are real and catastrophic.

But it is equally unserious to pretend that sanctions are a morally clean tool that only harms elites.

The U.S. under Trump stopped importing Venezuelan crude after the 2019 sanctions on PDVSA, even though Venezuelan oil had previously been significant for U.S. Gulf Coast refining systems. In 2018, U.S. imports from Venezuela averaged about 505,000 barrels per day—and then dropped to essentially zero after sanctions.

The sanctions literature is divided in important ways:

Broad sanctions scholarship has long argued that sanctions often fail to coerce policy change and can create perverse political effects.

On Venezuela specifically, one prominent estimate argued that sanctions worsened civilian mortality and living conditions and contributed to excess deaths, presenting sanctions as collective punishment.

Other analyses dispute the magnitude and causal claims, emphasizing that Venezuela’s structural decline preceded the harshest measures, and that mismanagement and institutional collapse are central drivers.

Even with disagreements, one conclusion is hard to avoid: sanctions are not neutral. They shape access to finance, spare parts, diluents, shipping insurance, payment systems, and investment—exactly the arteries an oil-dependent economy needs to function.

Which is why the new posture—“the economy failed, therefore we must run it”—feels like a political sleight of hand. If you help tighten the tourniquet, you don’t get to present yourself as the surgeon.

Here’s the argument I can’t shake: the Trump-era approach created a story where the United States could claim Venezuela’s economy “failed” and then present “running” the country as the rational solution—despite Venezuela’s massive resource base.

I can’t read the import cutoff, the pressure strategy, the asset controls, and the sanctions architecture as neutral instruments. They were built to deny the state oxygen—especially the oxygen that comes from oil revenue and financial access. Whether the intention was explicitly “destroy the economy” or “force capitulation regardless of civilian cost,” the functional result is similar: an economy with huge resources becomes an economy that cannot convert those resources into stability. And then the collapse is presented as proof that the state is unfit—an invitation for external management.

That rhetorical move—break it, then cite the brokenness as justification—is not new in intervention history. What’s new is how openly it has been said this time.

Canada and Mexico: America’s biggest oil suppliers—and also targets of Trump’s pressure politics

There’s another uncomfortable layer: even as Trump has treated oil as the prize in Venezuela, his administration has also used coercive economic tools against America’s biggest oil suppliers.

Canada and Mexico supply the bulk of U.S. crude imports—Canada alone is often around 60% of U.S. crude imports, with Mexico also a major supplier. [16] And yet Trump repeatedly threatened—and then imposed—major tariffs on both countries, using emergency-style logic to justify them. Even Canadian energy was hit with a tariff (lower than the general rate, but still a tariff). [17][18][19]

This matters for my “oil logic” argument: if a government is willing to pressure and threaten its own top energy suppliers, it tells me the energy story isn’t “we need friendly oil partners.” It’s “we will use energy and trade dependence as leverage”—even within supposedly stable North American interdependence.

Nigeria: counterterror language, energy geography, and the pattern of “strategic coincidence”

When U.S. strikes hit Nigeria on Christmas Day 2025, priests and reverends in Christian churches praised the massacre as "the best Christmas present". The public justification was counterterror logic. Trump claimed that in cooperation with the Nigerian government, he targeted "Christian killers", but international analysts of the region wonder why he chose to attack a newly formed group in a muslim populated area that attacks primarilly muslims, instead of the notorious Bogo Haram.

But Nigeria’s status as Sub-Saharan Africa’s largest crude oil producer and the global leader in unused reserves means its stability and orientation will always attract strategic attention. I’m not claiming straightforwardly that oil “caused” those strikes. I am saying oil changes the stakes—and it makes “completely unrelated coincidences” harder to swallow when the same administration is simultaneously talking about “taking back” oil elsewhere. [20]

The UK’s energy dependence complicates the moral theatre

If I’m honest, I find it naive to discuss Venezuela as if only Washington has been “thinking ahead.” The UK sanctioned Venezuelan figures linked to Maduro’s contested rule—and, crucially, London established a “Venezuela Reconstruction Unit” inside the Foreign Office system years before the 2026 strike. [11][12][13]

I’m not saying a small unit in Whitehall “caused” the raid. I am saying it tells me something about intent: parts of the international ecosystem were planning for a post-Maduro Venezuela as a project—administrative, financial, and geopolitical—well before the intervention crossed the line into open force.

One more layer makes the European posture feel even more “curious” to me: Britain’s biggest source of imported crude in 2024 was the United States, accounting for over a third of UK crude imports (with Norway close behind). [21] That’s not a moral argument; it’s a structural one. When your energy supply is tied tightly to Washington, your willingness to confront Washington’s use of force tends to shrink—no matter how elegant your statements about international law are.

That matters because it helps explain the choreography of “distance” and “alignment”: formally not involved, materially synchronized, structurally dependent.

Venezuela’s oil isn’t an ATM—so “taking it” implies a long (and inherently violent) political project

There’s another inconvenient truth: Venezuela’s oil sector is widely described as degraded and expensive to rebuild, with estimates in the public domain that imply huge investment and long time horizons. [22] So when leaders talk about oil as if it’s immediately collectible, they’re either selling a fantasy—or implying something else: control of the revenue channel, restructuring the sector, and shaping the political future.

That is why oil interests and regime change fuse so easily here. In a petrostate, controlling oil governance is not a side effect of political change. It is the heart of it.

The doctrine layer: a sphere-of-influence mindset isn’t hidden anymore

I can’t ignore the doctrinal context. A recent U.S. national security strategy document explicitly frames a Western Hemisphere “corollary” approach—treating the region as a zone where the U.S. intends to deny rivals control over strategically vital assets. [23]

That doesn’t automatically “cause” intervention. But it supplies something every intervention needs: a permission structure—the story a state tells itself about why it is entitled to act.

The uncreatively named "Donroe doctrine", comes as a predetermined but yet undetermined framework of military-infused geopolitical control of a whole hemisphere. It does not imply just the hegemony of the U.S. over a group of countries, but it resurrects the Cold War instability of the "balance of terror," and one may argue (many do) that it implies hegemony of the other hemisphere by the Russia-China coalition.

Legality: Start with the rule, not the personalities

I’m not going to pretend the legality question is unknowable. The UN Charter’s core prohibition is clear: members shall refrain from the threat or use of force against another state’s territorial integrity or political independence. [6]

There are narrow exceptions—Security Council authorization, consent, or self-defense under strict conditions. That means the legality debate—if taken seriously—turns on whether the action can plausibly fit self-defense, and whether its scale and objectives (strike-and-capture, follow-on coercive posture, plans to control proceeds) can satisfy necessity and proportionality.

If the world treats this as “hard to judge,” it isn’t because the rule is unclear. It’s because enforcement is political.

Even if the operation was tactically successful, the strategic risks are familiar:

Fragmentation: removing a leader doesn’t automatically create legitimate authority.

Security vacuums: irregular armed actors fill gaps quickly.

Economic shock: oil-sector reconstruction is slow, expensive, and politically explosive.

And the biggest risk is systemic: precedent. If cross-border capture plus economic control can be normalized, other powers will learn from it—either by copying it or by building countermeasures.

Bottom line

This is why I call it a curious case. Not because it’s hard to categorize, but because the world is behaving as if categorization is optional.

I see an intervention that fits two long-running pillars—regime change and energy leverage—with the added twist that the rhetoric has become unusually explicit. I see a legal order that depends on rules being treated as rules, not as suggestions. And I see a media-diplomatic ecosystem that often treats “legitimacy” as a debate about personalities rather than a question about constraints.

If I let the “curious case” framing become a substitute for clarity, I’m not just debating Venezuela. I’m rehearsing the future.

Main sources:

[1] Reporting on Maduro’s U.S. court appearance and plea (Jan 2026). (AP News)

[2] Additional reporting on the capture/transfer and first court appearance (Jan 2026). (The Guardian)

[3] Reuters-linked reporting on Venezuelan oil shipments to the U.S. and sanctions easing (Jan 2026). (Reuters)

[4] Reporting describing U.S. intent to control Venezuelan oil sales “indefinitely” and hold proceeds in U.S.-controlled accounts (Jan 2026). (The Guardian)

[5] AP reporting on seizure/management of Venezuelan oil and U.S.-approved channels (Jan 2026). (AP News)

[6] UN Charter Article 2(4) prohibition on threat or use of force.

[7] Venezuela proven reserves (~303 bn barrels) context. (U.S. Energy Information Administration)

[8] Background reference on 1953 Iran coup.

[9] Background reference on Iran–Contra/Nicaragua.

[10] EO 13692 (2015) Venezuela national emergency framework.

[11] UK government sanctions announcement (Jan 2025). (GOV.UK)

[12] UK Parliament written question on “Venezuela Reconstruction Unit” established in 2019. (UK Parliament Questions and Statements)

[13] Reuters report on UK sanctions aligning with U.S./EU posture (Jan 2025). (Reuters)

[14] EIA statement: U.S. crude imports from Venezuela stopped shortly after Jan 2019 PDVSA sanctions. (U.S. Energy Information Administration)

[15] EIA “Today in Energy” context on import halt and later limited resumption. (U.S. Energy Information Administration)

[16] Congressional Research Service: Canada and Mexico supply the bulk of U.S. crude imports. (Congress.gov)

[17] White House fact sheet on tariffs on Canada/Mexico, including lower tariff on Canadian energy resources. (The White House)

[18] Reuters on tariff threats/implementation against Canada and Mexico. (Reuters)

[19] CRS tariff actions timeline (tariff executive order details). (Congress.gov)

[20] Reuters on Nigeria’s oil production rank relative to the region (used to support “Nigeria largest” framing). (GOV.UK)

[21] UK government energy statistics (DUKES): U.S. provided over a third of UK crude imports in 2024. (GOV.UK)

[22] Reporting/analysis on degraded state of Venezuela’s oil sector and scale of rebuilding costs (Jan 2026). (The Guardian)

[23] U.S. 2025 National Security Strategy “corollary” framing for Western Hemisphere.